Simple scorekeeping isn’t enough…

Simple scorekeeping isn’t enough…

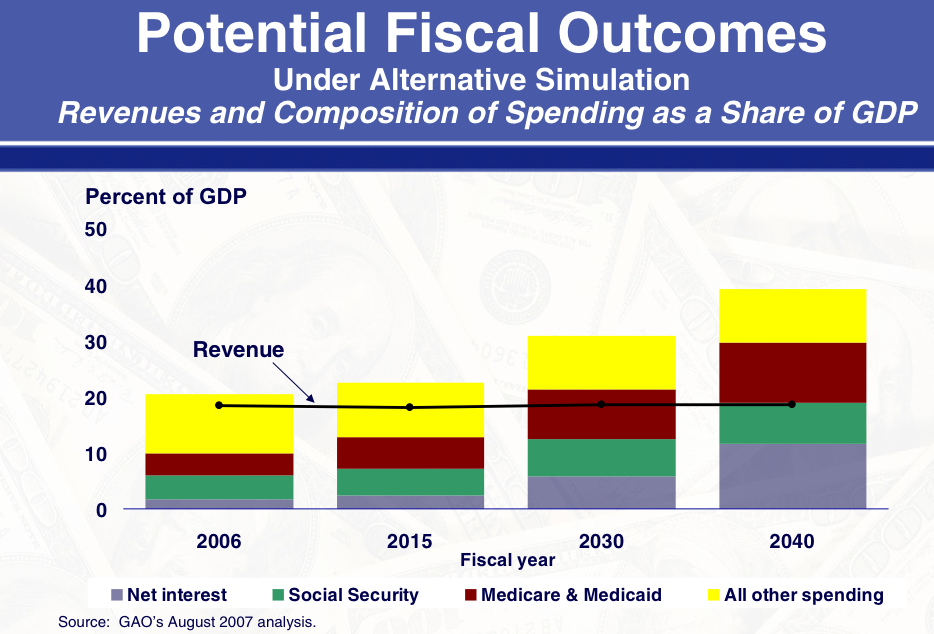

I am always amazed at the number of organizations that equate Performance Management with measuring only business results and a handful of supporting KPI’s, and calling it quits. Performance Management is much more than that, and I would argue that if that is the extent of your PM program, you have a pretty good chance of doing more harm than good.

I guess we’ve all gotten caught up with the notion of keeping things simple–seeing the “forest through the trees” if you will. And there is some merit to that type of thinking. After all, it’s difficult to manage at the strategic level when the organization measures too many seemingly irrelevant things. And there is no shortage of “experts” in the field preaching about the importance of limiting the number of KPI’s and “optimal” numbers of business metrics. To some extent, I agree with their argument that a highly focused set of KPI’s is essential to a good PM program. But it doesn’t stop there.

If you’re a regular golfer like me, you certainly track your scores over time. After all, you can’t get better if you don’t track your results. This is the business equivalent of your annual P&L and quarterly earnings trends.

Good KPI’s also tell us about the “drivers” of your success…

But if you play often enough, and aspire to get better, you’ll undoubtedly do more than that. You’ll begin to track things like “% of fairways hit”, “number of greens in regulation”, “average putts per hole”, “up and downs”, etc. Every sport has its key statistics, just like every business has its Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s). In fact, many golfers now track these statistics on their “Sky Caddies” or mobile phones in real time, just like most businesses now track their KPI’s on a myriad of desktop and mobile applications that are available for that purpose.

But for most golfers, and for many businesses, that is where their PM stops. Sure, we all do things to get better and “manage our performance” over time. In golf, we practice and practice more. We spend hours at the driving range hitting balls. We read countless magazines, watch instructional videos, and pay others to “fix” our swings. In business, we train and coach our staffs, improve our work environments, redesign our processes, and invest in new equipment and technology in pursuit of getting better. But in terms of tracking our progress, many of us still revert to the same limited suite of KPI’s to tell us whether we’re improving or not.

Are good KPI’s enough?

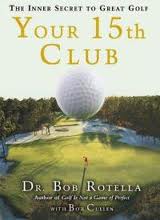

A few weeks back, I read Bob Rotella’s new book called “the 15th club”. Bob is a renowned sports psychologist who has coached many of today’s tour professionals–not on the mechanical elements of their game, but on the mental aspect required for peak performance. I’ve referenced his work in some of my past posts, like “progress over perfection,” because of the strong parallels I see between his teachings and corporate performance management.

One of the key points Bob makes in his latest book is the difference between how good golfers and bad golfers think about their shots, and what they spend their time measuring and tracking. As any golfer (beginner or professional) knows, “thinking” about a shot, both before and after its execution is inevitable. It’s WHAT you focus on that’s important.

When most of us hit a good or bad shot, we think about its impact on our round. Maybe we ponder the effect the shot will have on our statistics. We “shank” a ball into the trees and translate that into hitting one fewer fairway. We miss a long putt and worry about the impact it will have on our putting average. It’s hard not to look at each failure through the lens of the impact it will have on our overall results. It’s only natural. People around us will tell us to “shake it off” and stay positive. Well, the fact is that human emotions don’t easily allow for that. More often than not, we retain that thinking, allowing it to work itself into future shots and future rounds. One bad shot leads to more. It’s how good golfers get into slumps. Most golfers who play regularly know how to strike a golf ball (they’ve done it hundreds of times), yet it’s not uncommon to see some really ugly shots repeat themselves several times during a round, and for that ugliness to then continue into future rounds.

Measuring HOW you execute is often just as important as the results…

Rotella doesn’t preach the mantra of just “shaking it off”. Instead, he proposes new things to focus on and measure. His premise is that even the pros only hit a few “perfect shots” per round. After all, golf (and life) is not a game of perfection. The key is recovering after a bad shot and finding creative ways to score amidst the imperfection. After a bad shot, he suggests exploring the things that are essential to a good shot. Did I go though my pre-shot routine? Did I choose my target well? Did I visualize the trajectory I wanted? Did I finish my swing? If I did, and the shot did not execute well, then accept it and move on. Sure, there are times where the fundamentals may be broken, but that’s for your practice time, not in the middle of a round. In competition, you work with what you have, the strategy you select, and focus on whether you executed that strategy or not.

More often than not, measuring the things that are essential to good execution is as important as measuring the execution itself. In fact, thinking about the outcome DURING execution can actually be counter productive. It’s why most pro golfers try to not spend too much time looking at their stats or even the leader-board during the round.

More often than not, measuring the things that are essential to good execution is as important as measuring the execution itself. In fact, thinking about the outcome DURING execution can actually be counter productive. It’s why most pro golfers try to not spend too much time looking at their stats or even the leader-board during the round.

Measuring critical behaviors and practices…

In business, it’s just as important to measure the parts of a process or activity as it is to measure the outcomes. In fact, good companies often measure the presence or absence of specific instances of certain behaviors essential to success.

When it comes to safety performance, good companies have gone beyond simple reporting of lost time and “recordable” events, and even beyond things like “near misses” (all valuable KPI’s). In addition, they look at the presence or absence of safe behaviors and practices. Good call centers go beyond measuring transaction times and satisfaction levels and now look at whether the rep demonstrated certain behaviors that are linked to a successful resolution of an inquiry. If your plan is a good one, and you understand how specific practices and behaviors drive your results, then measuring those behaviors is often as important than the result itself.

Good companies trust their strategies, processes and policies to produce the outcomes they desire and measure their effectiveness at adhering to those activities. If they don’t produce the specific business outcome, then they will undoubtedly go back to the drawing board and evaluate whether the plan was a good one and redesign if necessary. But they won’t do this in the middle of execution just as good golfers don’t do it in the middle of competition.

This may sound a little like I am opposing the very flexibility that is needed for managing in real time, and enabling in-situ course corrections. But that’s not my intent. In fact, what I’m saying is that you should have a set of execution measures and ways of thinking that will help you focus on the right things during execution rather than doing that by the “seat of your pants” and relying on a distant set of KPI’s to navigate that process.

A good performance management system starts with the right goals, objectives, and KPI’s. But these KPI’s will not help you manage the execution of your strategy and focusing on them DURING execution will often cause more harm than good. Instead, measure the behaviors and actions that were part of your strategy even if specific day-to-day outcomes don’t pan out exactly like you envisioned. Only then will you be able to consistently execute and determine if your plan is working, and whether or not it needs retooling.