The one thing that most everyday drivers fear is that infamous “check engine light”. Unless its during the first few seconds of startup (the point at which every indicator on the dashboard lights up for a few seconds), a “check engine” alert is one of the few that signals that indicate big problems are imminent unless something changes fast…as in, stop the car soon and diagnose, or run the risk of being abandoned on the highway with a very costly repair. If you are someone who doesn’t take your vehicle’s indicator lights seriously, trust me (from experience), this is not one you want to ignore.

The one thing that most everyday drivers fear is that infamous “check engine light”. Unless its during the first few seconds of startup (the point at which every indicator on the dashboard lights up for a few seconds), a “check engine” alert is one of the few that signals that indicate big problems are imminent unless something changes fast…as in, stop the car soon and diagnose, or run the risk of being abandoned on the highway with a very costly repair. If you are someone who doesn’t take your vehicle’s indicator lights seriously, trust me (from experience), this is not one you want to ignore.

Dashboards, Indicators, and Alerts…

There are many indicators around us that alert us to changes in status of a process, and deviation from what may be considered to be a “normal operating condition”. And the place where most of these indicators are visible is on our dashboards. Whether it’s the dashboard of your vehicle, the cockpit display on an aircraft, the bridge on a ship, or a control room in a power plant; it’s the one central place where status is monitored and response strategies are determined, most often by the operator of the asset.

Of course, these deviations from the norm that show up on our “dashboards” occur in varying degrees, and can signal very different things. A “service soon” indicator light your car dashboard is more “suggestive”, and usually means its time for an oil change or tune up. But you’ve generally got some time before it becomes a bigger issue. A “low fuel” indicator on the other hand, is a bit more significant, and usually means you’ve got a finite quantity of miles left before you are what we might call “SOL” (although I’ve tested this threshold on occasion and can attest to the fact that there is some (albeit small) “cushion” past 0 to rely upon). And then there is the “check engine” light that most often means PULL OVER ASAP ( as soon as safe and practical -but SOON).

I’m not sure about you, but I view the “check engine” light as analogous to to an “airspeed alert” that a pilot might get right before a stall condition, or a traffic alert he gets when another aircraft is within the allowed separation tolerance. You might not yet be “past the point of no return”, but you’re pretty darn close.

Dashboards and Scorecards: Is there a difference?

In the Performance Management discipline, we often hear people refer to the terms “Dashboard” and “Scorecard” rather indiscriminately, with little if any conscious distinction as to what they each connote. I’ve often avoided getting too “wound up” about this, because getting caught up in corporate “buzz phrases” and semantics can cause us to miss the bigger issues at play. But after reflecting on this a bit, I think the differences here are in fact worthy of some discussion. Not because the words themselves are super important, but because it is critical that both components (whatever you call them) need to be part of your EPM solution.

So here are is my take on the critical distinctions between the two:

- Purpose: Dashboards are about helping you navigate the journey. Scorecards are about how successful the journey was.

- Type of indicators included: Scorecards generally contain outcome results, Dashboards are usually comprised of leading or predictive indicators

- Timeframe: Scorecards are periodic and longer term (weekly, monthly, annual trends) in the review horizon, while Dashboards are shorter term and can even be real time

- Reaction– Scorecards should provoke next steps that involve introspection and analysis (drill downs, mining insights, etc.) where dashboards usually are designed to “signal” or “provoke” immediate actions or course corrections

- Targets– Scorecards usually report against a target, threshold or benchmark as a percentage gap and trend. Dashboards generally report metrics within or against tolerance ranges, outside of which signal a required change

As with anything, these are not hard and fast rules, but they should give you a sense of where I personally see the distinctions.

Sure, there are some grey areas here. Outcomes for some, may only be a part of a journey for others. There are also cases where an an outcome indicator might be so important that it is worth tracking in both places- on the dashboard AND the scorecard. For example, some car dashboards have an indicator that tells you what MPG you are getting out of your fuel consumption in real time. But while MPG would normally be an “outcome” metric (i.e.scorecard material), it may also be useful to some of us in watching the degradation or improvement to MPG as we change driving patterns (rapid “gunning” and braking, versus more constant speeds, for example).

Examples for the Fairway

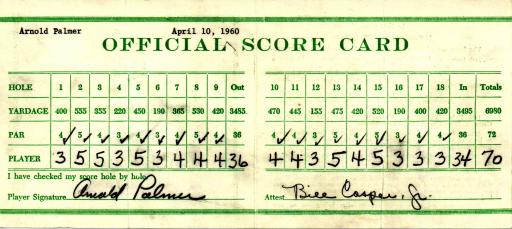

A few days ago someone posted about this same topic, using golf as their main analogy. And while I agreed with most of what he said, some of his examples created pause as I though of my time on the golf course.

We both agreed for example that the “stroke count versus par” was what you would always find on a conventional golf scorecard (hard to argue with that!). However, I would also say that stats like # of greens in regulation, puts per green, club distances, etc. should also be part of your scorecard, although maybe at a level or two down the chain. After all, these are things that need to be analyzed and challenged OFF the course (although I have been known to peak at them from time to time during the round). In fact, it is not uncommon for many golfers to track these very stats on their scorecard right underneath or beside their actual stroke count.

But if you put all of that on the scorecard, then what does the dashboard look like? We’ll if we think about it in terms of the 5 criteria I provide above, it would likely be things like yardages to the hole (what i need in order to  make my club selection), wind direction (what I need to shape my shot), # stokes ahead or behind the lead (what I need to manage my strategy), speed of the green (necessary in determining the line and speed of your putt), and the myriad of other factors that are utilized by professional golfers before and during a round. And while many of us may manage the above by “feel”, just take a look at a professional’s yardage book and caddy’s notes and you’ll see what looks strikingly similar to a dashboard (albeit manually illustrated with stray marks and notes). And if you want to spend the money, you can always buy some pretty cool dashboards for your iphone or blackberry.

make my club selection), wind direction (what I need to shape my shot), # stokes ahead or behind the lead (what I need to manage my strategy), speed of the green (necessary in determining the line and speed of your putt), and the myriad of other factors that are utilized by professional golfers before and during a round. And while many of us may manage the above by “feel”, just take a look at a professional’s yardage book and caddy’s notes and you’ll see what looks strikingly similar to a dashboard (albeit manually illustrated with stray marks and notes). And if you want to spend the money, you can always buy some pretty cool dashboards for your iphone or blackberry.

Some Final Thoughts…

I think some of the confusion between dashboards and scorecards is because metrics are often combined in the same visualization, regardless of whether it is called a scorecard or dashboard. Even automobile dashboards have a place for total accumulated miles. Golf GPS devices enable you to enter score count. As I said before, the distinction is sometimes burry, and often not even that critical.

What’s much more important is whether or not you have the full compliment of indicators you need to manage the business. When most executives ask their teams to develop “a dashboard”, the content of what they are really asking for is unclear. Are they hungry for better tracking of results? Or are they asking for better metrics- those that will enable better decisions and more responsiveness? Or are they simply looking for better analysis of the results?

Unless you understand that, it will be hard to deliver on any of these requests or mandates, regardless of what you end up naming it. In the end, Scorecards and Dashboards are merely visualization tools. What';s more important is that you embed and align the right content into these tools that will enable a clear line of sight between vision, objectives, KPI’s, metrics, and initiatives that tells the complete story and enables those who are in execution roles to be successful.

The bottom line is that you are the designer and architect of the info that is displayed, and so all these distinctions- whether it is between scorecard and dashboard, long term versus short term, leading versus lagging, etc.— are really only important in terms of their usefulness in helping YOU design a system that is relevant and useful within your organization. What you call these things is not near as important as whether the system produces the right outcomes.

Author: Bob Champagne is Managing Partner of onVector Consulting Group, a privately held international management consulting organization specializing in the design and deployment of Performance Management tools, systems, and solutions. Bob has over 25 years of Performance Management experience and has consulted with hundreds of companies across numerous industries and geographies. Bob can be contacted at bob.champagne@onvectorconsulting.com