Choosing your “strategic bias”…

We’ve had more than a few conversations with clients of late that revolve around the subject of core competency. What is it today? What should it be? What do we want it to be? Must we choose between product innovation, customer care, or operational excellence, or is it possible to have all three? While there isn’t a “one-size-fits-all” answer, the consensus philosophy (as espoused, for example, in the “The Discipline of Market Leaders”) is that there should most definitely be a bias toward choosing one axis of the model for optimization.

It certainly has been an issue that’s generated a lot of strategic debate in corporate boardrooms. Most provocative and paradoxical questions will do that. But the reason this debate so energizes meetings is because it also taps into something deeper–corporate culture and emotion. Operations, R&D, and Customer Service, among other departmental factions, continue to fight for precious budget and capital, and as these resources become increasingly constrained, the consequence of failing to “choose” begins to look like compromise or watered-down decision making. Clearly, it seems, steering a majority of our resources into one of these areas offers the opportunity to create some short-term wins in that area, but it also risks undermining our overall strategy, which could, in the end, leave us with nothing to show.

When a “bias” becomes “THE end game”…

Unfortunately, the very essence of what has made this discussion so valuable is, as well, now creating an unhealthy dynamic in some leadership circles. With resource constraints and the passions of business unit executives both reaching fever pitch, the push to make the core competency declaration is stronger than ever, and the tendency to push for a “clear choice” rather than just a “bias” (which was the original intent of the management model) is more often than not the desired end game of each of these respective operating executives (so long as its THEIR area that benefits from the increased emphasis).

Rather than focus on optimizing just one dimension of the business, we should, instead, look to companies that have managed to assemble the complete package, or, more accurately, perhaps an edge in one domain but without apparent sacrifices in the other two. Apologies in advance for more “Apple advocacy”, but clearly this is an example of a company that not only balances these three dimensions skillfully, but excels in them simultaneously.

Having your cake and eating it too…

Apple is clearly a product-based business…no argument there. Simplicity, functionality, user commitment, and advocacy … the list goes on. When people buy an Apple product, loyalty and advocacy are an integral part of each transaction, and this despite the fact that customers are sometimes even paying a premium price versus competing products. They are immediately reinforced by their “buy decision”. One of our clients calls this “smart value”–the ability of a company, through its product experience, to continuously remind each customer of how smart their purchase decision was. Worth noting also is the fact that, while Apple sells many premium-priced products, they offer, as well, a range of affordable ones that, despite their competitive prices, still feature the design and functionality excellence that customers have come to expect from the company. That their manufacturing and operational processes are sufficiently well-thought-through to allow such products to be offered is a testament to their emphasis on the operational side of the business.

On the customer-care side of things, they are equally credible, if not downright superior, for example, in the way their service channels are so perfectly aligned with customer convenience, the way they make and manage commitments and appointments, the almost cult-like enthusiasm of their staff, the customer-centric culture of their work environments. Even tasks that are traditionally frustrating to customers–warranty issues, software updates, etc.–are so smoothly handled that customers walk away having appreciated the experience.

Separate and apart from the fact that these stores generate more revenue per square foot than any company in history , what is more amazing is the customer-centric focus and attitude that are constantly on display. Whether it is the simplicity of making an appointment at the genius bar , the excellent service you receive, or nice little touches like bypassing the line and having an employee execute the transaction by hand-held device and email you the receipt, it’s all there. When was the last time you heard customers raving about an extra warranty plan for a product that rarely fails?

Product Innovation, Operational Excellence, Customer Advocacy … Walk into any Apple store and you’ll see all three in abundance.

Creating and multiplying your base of “engaged advocates”…

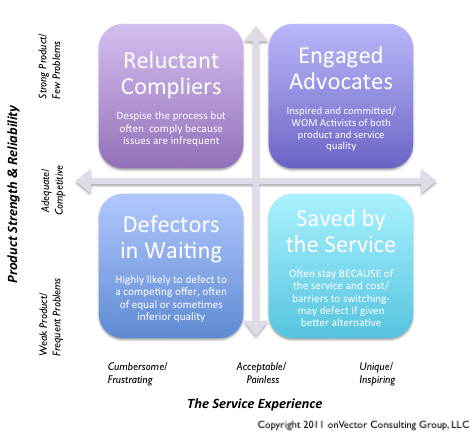

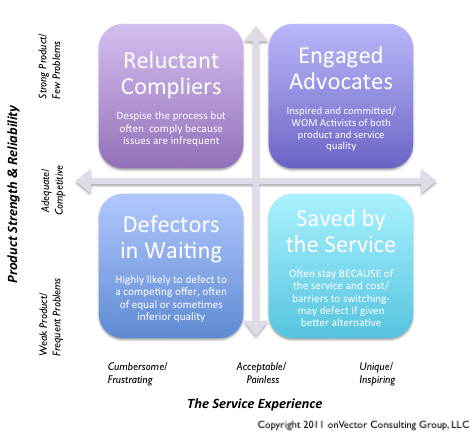

Recently, we’ve shared some views on the need to excel at both product and service experiences. (“Customer Nirvana”) Failure to achieve both means you are only creating temporary success, i.e., until customers have a better choice or option. The path to engaged advocacy requires both. And to achieve product and service excellence simultaneously, as well as profitably, requires operational excellence.

Recently, we’ve shared some views on the need to excel at both product and service experiences. (“Customer Nirvana”) Failure to achieve both means you are only creating temporary success, i.e., until customers have a better choice or option. The path to engaged advocacy requires both. And to achieve product and service excellence simultaneously, as well as profitably, requires operational excellence.

Strategic models that ask you to focus time and money on a single discipline certainly have their place. For example, if your company finds itself in the unfortunate position at being sub-par in all dimensions, then more often than not it will make sense to focus on fixing one area at a time. But as a long-term aspiration, maximizing all dimensions of performance remains the path to being recognized as world class.

There are many football teams that have either awesome offensive or defensive capabilities, but you rarely see any of them playing in the Super Bowl. It’s the team that has managed to strike a proper balance between the groups — offense, defense, special teams — that usually walks away with the trophy.

-b/b

About the Authors:

Bob Champagne is Managing Partner of onVector Consulting Group, a privately held international management consulting organization specializing in the design and deployment of Performance Management tools, systems, and solutions. Bob has over 25 years of Performance Management experience with primary emphasis on Customer Operations in the global energy and utilities sector. Bob has consulted with hundreds of companies across numerous industries and geographies. Bob can be contacted at bob.champagne@onvectorconsulting.com

Brian Kenneth Swain is a Principal with onVector Consulting Group. Brian has over 25 years of experience in Marketing, Product Management, and Customer Operations. He has managed organizations in highly competitive product environments, and has consulted for numerous companies across the globe. Brian is an alumnus of McKinsey & Company, Bell Laboratories, and Reliant Energy, and is a graduate of Columbia University and the Wharton Business School. He can be contacted at brian.swain@onvectorconsulting.com.

An end-to-end approach for managing customer experience strategy and delivering on its promises...

An end-to-end approach for managing customer experience strategy and delivering on its promises...

Reasonable behavior for a typical human, granted, but is it as reasonable to expect the same apparently irrational behavior pattern from a corporation, whose goals are presumably established in a more thoughtful (and usually sober

Reasonable behavior for a typical human, granted, but is it as reasonable to expect the same apparently irrational behavior pattern from a corporation, whose goals are presumably established in a more thoughtful (and usually sober  manner. Is it surprising that these goals often realize the same miserable success rates.?

manner. Is it surprising that these goals often realize the same miserable success rates.? At the end of the year, or any reporting period for that matter, we all want to be in a position to declare success on our initial goals for the year. And where we haven’t been successful, we want to at least have had ample opportunity to course-correct to get back on track, or deliberately declare a different target. What we don’t want is to miss the numbers and not know why. Again, sounds like a no brainer, but those kind of questions and blank stares still plague many business and operating executives when it comes to missed performance goals.

At the end of the year, or any reporting period for that matter, we all want to be in a position to declare success on our initial goals for the year. And where we haven’t been successful, we want to at least have had ample opportunity to course-correct to get back on track, or deliberately declare a different target. What we don’t want is to miss the numbers and not know why. Again, sounds like a no brainer, but those kind of questions and blank stares still plague many business and operating executives when it comes to missed performance goals.

Berkshire Hathaway, a company whose entire business is based on the prudent, sober, and wise investing of its founder, ended up the subject of one of 2011’s stories of financial impropriety–an insider trading scandal the likes of which we’ve come to expect from the industry, just not from these guys.

Berkshire Hathaway, a company whose entire business is based on the prudent, sober, and wise investing of its founder, ended up the subject of one of 2011’s stories of financial impropriety–an insider trading scandal the likes of which we’ve come to expect from the industry, just not from these guys.