Most of the projects I work on day in and day out involve data to varying degrees. I use data quite extensively in all of the assessments I do on organizational and operational performance. I use it heavily whenever I benchmark a company’s processes versus a comparable peer group. Data is at the very core of any target setting process. And, of course, data is (or at least should be) the beginning, and a continuous part of any gap analysis and any subsequent improvements that follows.

Today, the hunger that organizations have for good data has reached such unprecedented levels, that whole industries have developed in and around the domain of what we now call “Business Intelligence” or BI. Having consulted to organizations over the last three decades, I’ve seen this hunger level increase steadily throughout the entire period. But no more so than in the past few years.

However, despite all the gyrations that we’ve gone through over the years, one of the first things I hear from C-Suite Executives is that they still feel “Data rich and information poor”. So I’ll start this post off in the words of late President Ronald Regan by asking, “Are we better off or worse off than we were 4 years ago (in terms of translating data into useful and actionable information)?”

So are we better off than we were 4 years ago?

As any good politician, I would have to hedge a bit, and say yes, and no. And appropriately so I think.

We are most certainly better in our ability to “access” the data. If you’ve lived through the same decades as I have , you will remember the painstaking efforts we all made to extract data out of those proverbial “source systems” (when “SAS routines” had nothing to do with the SaaS of today). Everything from the data inside of our source systems, to the tools we use to access the data, to the ways in which we report and visualize the results has moved forward at lightening speed. And so, from that standpoint, we are, in fact, better off.

But on the other side of the coin, our tools have, in most cases, outpaced the abilities of our organizations and their leadership to truly leverage them. At a basic level, and in part because of the technology itself, we often have more data than we know what to do with (the proverbial “data overload”). Some would say that this is just a byproduct of how wide the “data pipe” has become. And at some level, that’s hard to argue.

But I think the answer goes well beyond that.

“Data rich, information poor”…still?

In large measure, yes. The bigger issue in my view is the degree to which the organization’s skills and cultural abilities enable (or better said, disable) them to effectively utilize data in the right ways. Most companies have put such a large premium on data quality and the ability to extract it through their huge investments in IT infrastructure and financial reporting, that it has in some ways forced leadership to “take it’s eye off the ball” with respect to the way in which that data is operationalized.

So from the perspective of using the data to effect smarter operational decisions, I’d say the successes are few and far between.

Of course, you can google any of the “big 3″ IT vendors and find a myriad of testimonials about how much better their decision making processes have gotten. But look at who’s doing the speaking in the majority of cases. It is largely from the Financial and IT communities, where the changes have been most visible. But it’s in many of these same companies where operating executives and managers still clamor for better data and deeper insights.

So while at certain levels, and in certain vertical slices of the business, the organization is becoming more satisfied with its reporting capabilities, translating that information into rich insights and good fodder for problem solving still poses a great challenge. And unfortunately, better systems, more data, and more tools will not begin to bridge that gap until we get to the heart of some deeper cultural dynamics.

Needed: A new culture of “problem solvers”

Early in my career, I was asked to follow and accept what appeared to me at the time to be a strange “mantra”: “If it ain’t broke, ASK WHY?” That sounded a little crazy to me having grown up around the similar sounding but distinctly different phrase: “If it aint’t broke, DONT fix it”.

That shift in thinking took a little getting used to, and began to work some “muscles” I hadn’t worked before. For things that were actually working well, began asking ourselves “why?”. At first, we began to see areas where best practices and lessons learned could be “exported to other areas. But over time, we quickly learned that what appeared to be well functioning processes, wasn’t so well functioning after all. We saw processes, issues, and trends that pointed to potential downstream failures. In essence, we were viewing processes that were actually broken, but appeared to be A-ok because of inefficient (albeit effective) workarounds.

That shift in thinking took a little getting used to, and began to work some “muscles” I hadn’t worked before. For things that were actually working well, began asking ourselves “why?”. At first, we began to see areas where best practices and lessons learned could be “exported to other areas. But over time, we quickly learned that what appeared to be well functioning processes, wasn’t so well functioning after all. We saw processes, issues, and trends that pointed to potential downstream failures. In essence, we were viewing processes that were actually broken, but appeared to be A-ok because of inefficient (albeit effective) workarounds.

“Asking why?” is a hard thing to do for processes that appears to be working well. It goes against our conventional thinking and instincts, and forces us to ask questions…LOTS of questions. And to answer those questions requires data…GOOD data. Doing this in what appeared initially to be a healthy process was at first difficult. You had to dig deeper to find the flaws and breakdowns. But by learning how to explore and diagnose an apparently strong processes, doing that in an environment of process

failure became second nature. In the end, we not only learned how to explore and diagnose both: The apparent “good processes”, and those that were inherently broken. And for the first time in that organization, a culture of problem solving began to take root.

Prior to that point, the organization looked at problems in a very different way. Performance areas were highlighted, and instinctively management proceeded to solve them. Symptoms were mitigated, while root causes were ignored. Instead of process breakdowns being resolved, they were merely transferred to other areas where those processes became less efficient. And what appeared to be the functioning parts of the business, were largely overlooked, even though many of them were headed for a” failure cliff”.

Indication, Analysis, and Insight

Few organizations invest in a “culture of problem solving” like the one I describe above. Even the one I reference above, deployed these techniques in a selected area where leadership was committed to creating that type of environment. But throughout industry, the investment in generating these skills, abilities and behaviors across the enterprise, pales in comparison to what is invested annually in our IT environment. And without bringing that into balance, the real value of our data universe will go largely unharvested.

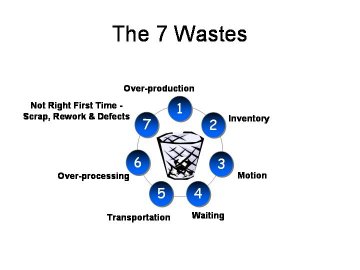

There are a myriad of ways a company can address this. And some have. We can point to the icons of the quality movement for one, where cultures were shaped holistically across whole enterprises. More recently, we’ve seen both quality and efficiency (more critical to eliminating waste and driving ROI) get addressed universally within companies through their investments in the Six Sigma, and more recent Lean movements.

But if I had to define a place to start (like the business unit example I described above), I would focus on three parts of the problem solving equation, that are essential to building the bridge toward a more effective Enterprise Performance Management process.

- Indication– We need to extend our scorecards and dashboards to begin covering more operational areas of our business. While most of us have “results oriented” scorecards that convey a good sense of how the “company” or “business unit” is doing, most have not gone past that to the degree we need to. And if we have, we’ve done it in the easier, more tangible areas (sales, production, etc). Even there however, we focus largely on result or lagging indicators versus predictive or leading metrics. And in cases where we have decent data on the latter, it is rarely ever connected and correlated with the result oriented data and metrics. How many companies have truly integrated their asset registers and failure databases with outage and plant level availability? How many have integrated call patterns and behavioral demographics with downstream sales and churn data? All of this is needed to get a real handle on where problems exist, or where they may likely arise in the future.

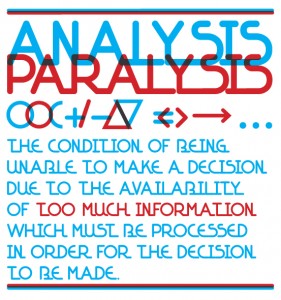

Analysis– When many companies hear the word “analysis”, they go straight to thinking about how they can better “work the data” they have. They begin by taking their scorecard down a few layers. The word “drill down” becomes synonymous with “analysis”. However, while they each are critical activities, they play very separate roles in the process. The act of “drilling down” (slicing data between plants, operating regions, time periods, etc.) will give you some good indication where problems exist. But it is not “real analysis” that will get you very far down the path of defining root causes and ultimately bettersolutions. And often, it’s why we get stuck at this level. Continuous spinning of the “cube” gets you no closer to the solution unless you get there by accident. And that is certainly the long way home. Good analysis starts with good questions. It takes you into the generation of a hypothesis which you may test, change and retest several times. It more often than not takes you into collecting data that may not (and perhaps should not) reside in your scorecard and dashboard. It requires sampling events and testing your hypotheses. And it often involves modeling of causal factors and drivers. But it all starts with good questions. When we refer to “spending more time in the problem”, this is what we’re talking about. Not merely spinning the scorecard around its multiple dimensions to see what solutions “emerge”.

Analysis– When many companies hear the word “analysis”, they go straight to thinking about how they can better “work the data” they have. They begin by taking their scorecard down a few layers. The word “drill down” becomes synonymous with “analysis”. However, while they each are critical activities, they play very separate roles in the process. The act of “drilling down” (slicing data between plants, operating regions, time periods, etc.) will give you some good indication where problems exist. But it is not “real analysis” that will get you very far down the path of defining root causes and ultimately bettersolutions. And often, it’s why we get stuck at this level. Continuous spinning of the “cube” gets you no closer to the solution unless you get there by accident. And that is certainly the long way home. Good analysis starts with good questions. It takes you into the generation of a hypothesis which you may test, change and retest several times. It more often than not takes you into collecting data that may not (and perhaps should not) reside in your scorecard and dashboard. It requires sampling events and testing your hypotheses. And it often involves modeling of causal factors and drivers. But it all starts with good questions. When we refer to “spending more time in the problem”, this is what we’re talking about. Not merely spinning the scorecard around its multiple dimensions to see what solutions “emerge”.- Insight– I’d like to say when you do the above two things right, insights emerge. And sometimes they do. But more often than not, insights of the type and magnitude we are looking for are usually not attainable without the third leg of this problem solving stool. Insight requires its own set of skills which revolve around creativity, innovation, and “out of the box” thinking. And while some of us think of these skills as innate, they are very much learnable. But rather than “textbook learning” (although there are some great resources on the art of innovation that can be applied here), these abilities are best learned by being facilitated through the process, watching and learning how this thought process occurs, and then working those skills yourself on real life problems.

Dont forget “line of sight”

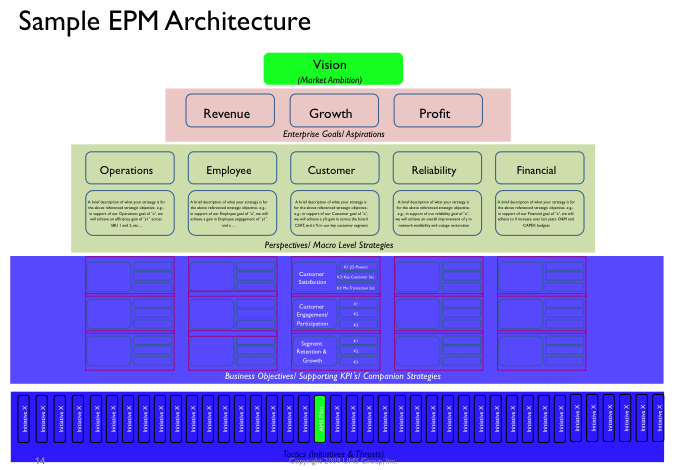

A few days ago I wrote a post on the concept of “line of sight” integration of your performance management content and infrastructure. It’s important here to reinforce the importance of tracking all of this back to that underlying construct.

The process of operationalizing information, is but one of many in the “line of sight” chain from your company’s vision, to the operational solutions that manifest here. And this process of operationalizing change is only a beginning of the journey you will make to translating these gains into ROI for the business (what I’ve referred to before as “value capture” or “value release”).

So as you navigate your path through the above activities, its useful to keep it in context and remember that the desired end state is to enable your business to see that clear “line of sight” from the very top of the organization right down to the work-face.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

There’s not enough space in a post like this to elaborate as much as we could on each of these. And creating real cultural change clearly involves more than a few quick bullet points. But as has been my tradition in this blog, my intent is to introduce you to principles and techniques that can get you started on this journey, or increase the ability for you to navigate the road your on.

Author: Bob Champagne is Managing Partner of onVector Consulting Group, a privately held international management consulting organization specializing in the design and deployment of Performance Management tools, systems, and solutions. Bob has over 25 years of Performance Management experience and has consulted with hundreds of companies across numerous industries and geographies. Bob can be contacted at bob.champagne@onvectorconsulting.com

One of the questions I get asked often by my clients is “just how many KPI’s and metrics are enough for effective Performance Management to occur?”

One of the questions I get asked often by my clients is “just how many KPI’s and metrics are enough for effective Performance Management to occur?”