Regardless of whether you’re a racing fan or not, chances are you’ve seen the below video as it made its social media rounds last year. As a junkie for organizational agility and speed, I never get tired of watching it. And if you haven’t seen it, by all means take a look, as it speaks volumes about today’s topic.

Those of us who spend time in and around Customer Service organizations see our fair share of big investments—new IT deployments, reengineering of back-office processes, upgrading our contact centers … the list goes on. With the introduction of each new Customer Experience (Cx) program, the size of the investment portfolio grows even further through projects like enterprise-wide journey mapping, training initiatives, new service channels, and improvements to research and data analytics platforms. Big projects are a reality for CCO’s and their leadership teams, and justifiably so. Maintaining customer support infrastructure is undoubtedly key to our long-term success.

But are we putting too much emphasis on our customer infrastructure at the expense of the smaller and more actionable practices that could generate more immediate results?

When Smaller is Better…

When asked to describe their Customer Experience initiatives, many CCO’s point to the “small stuff” as being key to the results they’ve achieved. In a world where everyone talks about “Big”—big data, big projects, big commitments—it’s these small, seemingly insignificant, practices, with not-so-small impacts, that are becoming the poster children of their efforts.

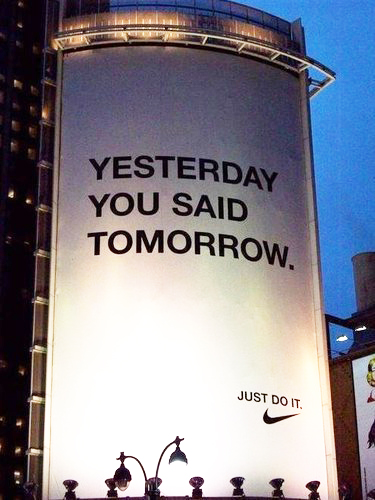

I’m talking about practices that don’t require an “act of congress” to implement—the ones that are just good common sense and take next to nothing to implement, except a little foresight and follow-through. Simple and easy, yet, still, an overwhelming number of organizations focus on the big solution being implemented and, in doing so, miss the opportunities to make a difference today.

Consider call/contact centers for a moment, where “big stuff” always takes center stage. How often do we hear “When our new CIS is in place,” “As soon as we implement speech analytics,” “Once we get that new IVR,” etc. But the reality is that most of what we need to make incremental—and sometimes big—changes is already there for those with the creative energy to act on it.

Fix-it-Fridays

A past client (We’ll call her Sarah), one I still regard as a brilliant Customer Service manager, was excellent at demonstrating this concept, i.e., using what she had available at her disposal today, combined with a real action bias to catalyze big change. One of my favorites was a practice she called “Fix-it Fridays.”

During the week, she would mine a few recorded calls for good examples of customer interactions that were “less than optimally handled.” This could mean the rep simply misunderstood the customer’s issue and employed an ineffective solution, or that a good solution was just poorly delivered and/or executed.

Each Friday afternoon, she would get small groups of reps together (voluntarily, but usually enticed with a bit of free food or cake) to brainstorm better ways of handling these customer situations. They would listen to a sample call together and discuss how the rep handled the interaction. Then they (not the supervisor, QA manager, or trainer, but the front line reps themselves) would talk about how they would approach the call differently. Challenge and debate were encouraged. But it was also a safe and rewarding experience that left everyone, including the rep in the “case study,” feeling better equipped to deliver on their Cx commitment. As this manager used to say, “it’s a little like looking in the mirror when you apply your own service standards to the responses we deliver day in and day out.”

Many organizations use some variation of this in their centers. Nearly everyone has a QA/monitoring process in place (although many place their focus on procedural and policy compliance rather than emerging Cx values and standards). Most have decent follow-up mechanisms for supervisor coaching when problems occur. And (most of the time) when broad themes emerge, they work them into their ongoing training. But all of this takes time. And, increasingly, such efforts rely on technology and infrastructure to mine interactions, which often means more time and complexity.

Sarah’s approach was focused on “time to market.” It didn’t discount the value of the existing process or the opportunities new technology can offer. Rather, it simply looked for ways to act more quickly. Perhaps, more importantly, she used her weekly forums as a way to teach staff how their Cx standards really were being applied, by immersing them directly, and by letting the team explore those standards in real time. The focus wasn’t on developing new policies or approving new scripts. It was about learning and applying good Cx.

Your reaction to this may be that you achieve these results through your QA process and ongoing coaching. But before your discount Sarah’s practice as run-of-the-mill, ask yourself:

- How long does it take employees in your organization to act on a solution once it’s identified?

- Do you encourage bad practices to be changed on the spot, sometimes on the basis of good instinct or common sense, or do all changes have to go through your business improvement processes and protocols?

- Once a new approach is identified, how quickly is it shared and institutionalized?

- Do your managers and staff feel empowered to take risks and deploy changes quickly?

- Are small “experiments” allowed, knowing that most can be “unwound” if they prove to be less effective than anticipated?

Examples like this abound throughout our customer service organizations—process fixes,touchpoint improvements, intelligence gathering techniques, and many more. And there is no doubt that the projects and initiatives we have in place to deal with these challenges will lead us to a more consistent and sustainable application of our Cx strategy. But without an equally ambitious focus on the smaller solutions, and a bias from the organization to support them, they simply won’t happen.

Commit today to making the small stuff an equal priority within your company. Ask for it, reward it, and manage to it. The wins may seem small at first, but stack up enough of them and you’ll discover stronger momentum and a faster ROI on your Cx investment.

Bob Champagne is Managing Partner at onVector Consulting. Bob has over 25 years designing and delivering performance management and governance solutions at the Enterprise and Business Unit levels of the organization. Bob can be contacted at bob.champagne@onvectorconsulting.com or through LinkedIn at http://www.linkedin.com/in/bobchampagne onVector’s Line of Sight solution suite has been utilized by its client organizations to establish the critical linkages between strategies, initiatives and KPI’s; enabling better alignment, higher levels of performance and a faster path to ROI. onVector’s Line of Sight methodology has been adapted to facilitate the unique management and governance needs of many strategic initiatives across the organization, including Customer Experience.To learn more about Cx Solutions available through onVector, including:

- Cx Readiness Assessments

- Cx Program Startups

- Cx Alignment & Standards Development

- Rapid Touchpoint Renewal

- Cx Management & Governance Solutions

visit us at http://onvectorconsulting.com/cxsolutions

An end-to-end approach for managing customer experience strategy and delivering on its promises...

An end-to-end approach for managing customer experience strategy and delivering on its promises...

Reasonable behavior for a typical human, granted, but is it as reasonable to expect the same apparently irrational behavior pattern from a corporation, whose goals are presumably established in a more thoughtful (and usually sober

Reasonable behavior for a typical human, granted, but is it as reasonable to expect the same apparently irrational behavior pattern from a corporation, whose goals are presumably established in a more thoughtful (and usually sober  manner. Is it surprising that these goals often realize the same miserable success rates.?

manner. Is it surprising that these goals often realize the same miserable success rates.? At the end of the year, or any reporting period for that matter, we all want to be in a position to declare success on our initial goals for the year. And where we haven’t been successful, we want to at least have had ample opportunity to course-correct to get back on track, or deliberately declare a different target. What we don’t want is to miss the numbers and not know why. Again, sounds like a no brainer, but those kind of questions and blank stares still plague many business and operating executives when it comes to missed performance goals.

At the end of the year, or any reporting period for that matter, we all want to be in a position to declare success on our initial goals for the year. And where we haven’t been successful, we want to at least have had ample opportunity to course-correct to get back on track, or deliberately declare a different target. What we don’t want is to miss the numbers and not know why. Again, sounds like a no brainer, but those kind of questions and blank stares still plague many business and operating executives when it comes to missed performance goals.

Build in the “small stuff” where it matters most

Build in the “small stuff” where it matters most

Berkshire Hathaway, a company whose entire business is based on the prudent, sober, and wise investing of its founder, ended up the subject of one of 2011’s stories of financial impropriety–an insider trading scandal the likes of which we’ve come to expect from the industry, just not from these guys.

Berkshire Hathaway, a company whose entire business is based on the prudent, sober, and wise investing of its founder, ended up the subject of one of 2011’s stories of financial impropriety–an insider trading scandal the likes of which we’ve come to expect from the industry, just not from these guys.