As a follow up to my post yesterday, and my recent attempts to expand our thinking on what Enterprise Performance Management really is, I’ll focus a little bit on another integral part of the collective whole- the “analytic and problem solving” side of the equation.

My thinking on this was triggered largely by a twitter post I received yesterday which read “Why is Performance Management focused on measurement & control – it should release performance rather than trying to contain it”. I believe the tweet was actually zeroing in on the “contain and control” element of some of today’s more popular business improvement frameworks, viewing their thinking as somehow contradictory to actually building value …kind of suggesting an “either/ or” mindset. But the more I reflected on it, I realized that, for me, this was more of an “and/both” issue. Let me explain…

There are many problem solving frameworks out there when it c

omes to business improvement, but one of the most common approaches is built upon the Lean and Six Sigma disciplines- a collection of problem solving and analysis tools and practices which have emerged in many organizations across the globe in the past decade as the business improvement philosophy of choice.

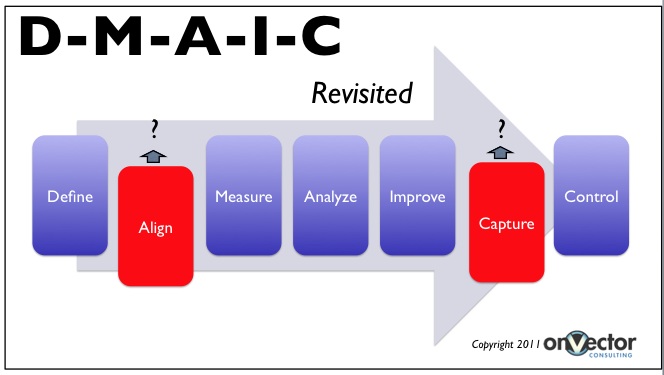

One of the many tools applied by the Lean community when approaching a business problem is what they call D-M-A-I-C (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control). You can also find this principle within many other business improvement frameworks, but its roots reside in some of the very early thinking in the development of the Lean, Six Sigma and related improvement/ quali

ty methodologies. I’ve kind of always viewed DMAIC as an extension of the old Plan-Do-Check-Adjust model, but I’m sure some of the Lean purists would probably take issue with that, and I certainly can’t debate that. What I can tell you is that these kind of tools and mental models do work, and help greatly in demystifying and putting a problem into a bigger and more relevant context.

But in my view, it does fail to capture two critical dimensions:

- The importance of alignment- I’ve discussed this at length in some of my previous posts (securing alignment), but suffice it to say, it is one of the main reasons that strategies fail, and that KPI’s that are viewed as critical by management, often get ignored. Simply defining the business objective or problem statement and jumping straight to the measurement aspect seems to miss the importance of the alignment that is required before the problem can be attacked head on with maximum commitment from the team.

- The importance of Value Capture (or what I often refer to as value RELEASE)- There is some good thinking that is emerging in this area, and I encourage you to explore it. But the key implication us that if we don’t put a high degree of emphasis on capturing the value (“ringing the cash register” in some way), then all we have really engaged in is a philosophical or analytic exercise. Whenever I see pockets of an organization deploying Lean based tools, without significant involvement from the CFO and budgeting functions (which is the primary control mechanism to capture, contain, and ensure value is released), I get concerned. See my EOY review of EPM trends (bullet #3) for a discussion of this)

I am certainly not proposing another itteration of DMAIC or PDCA, as these models have served us well over the years. And since philosophies like Lean, Six Sigma,and the older ones like TQM are the closest we’ve gotten to the kind of holistic approaches to EPM I recommend in yesterday’s post, we cant be too quick to dismiss some of their core tenets.

But I do submit that these two missing components – alignment and value capture– are too critical to be left out of the discussion, and simply embedded into the broader methodology. Like I suggested yesterday, our thinking often gets limited because of the nature of the disciplines and practitioners involved, and in this case we may be seeing the same thing. Lean thinking is highly analytical and problem solving oriented, and hence, some of its practitioners tend to place less emphasis on other complementary disciplines needed here: the human side of aligning leadership teams and employees, and the financial realism of actually releasing value on the back end of the cycle. And when that occurs, we can be left with the coolest mathematical equations, graphs and control charts, with little hope that value will actually accrue on the back end.

I’d like to hear your thoughts.

Author: Bob Champagne is Managing Partner of onVector Consulting Group, a privately held international management consulting organization specializing in the design and deployment of Performance Management tools, systems, and solutions. Bob has over 25 years of Performance Management experience and has consulted with hundreds of companies across numerous industries and geographies. Bob can be contacted at bob.champagne@onvectorconsulting.com